Reviewed by Paul Strother (Boston College Weston Observatory)

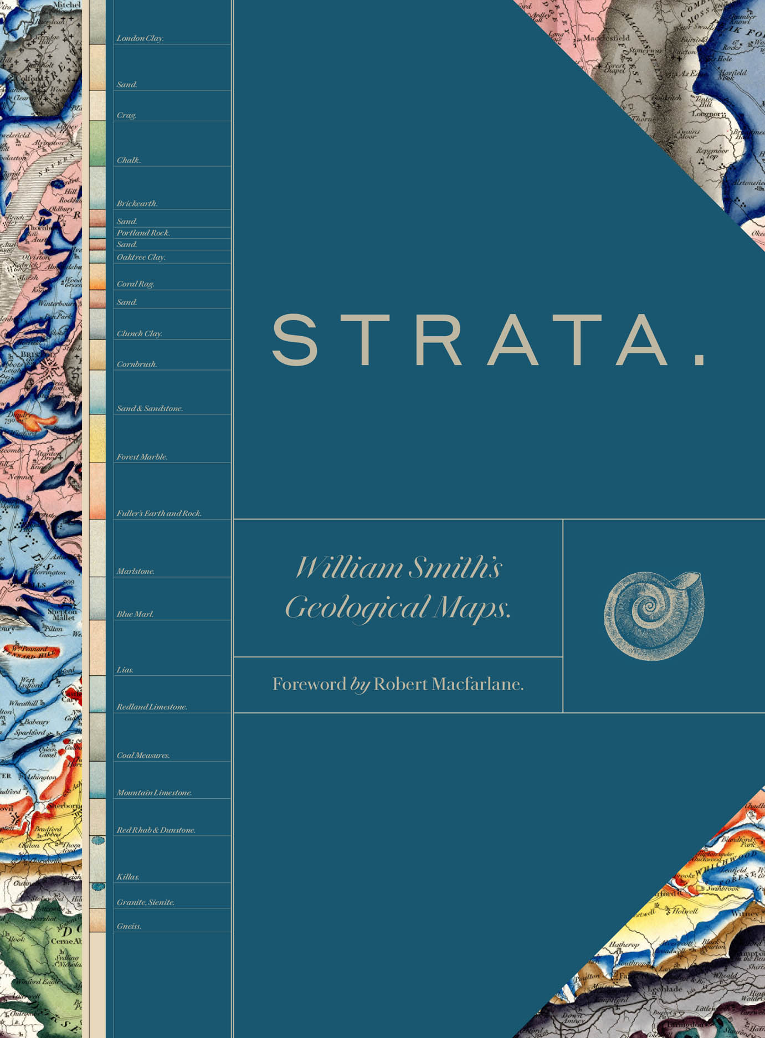

Oxford University Museum of Natural History, editor. 2020. Strata: William Smith’s Geological Maps.Univ. Introduction by D. Palmer, Foreward by R. Macfarlane. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 224 pp. ($39.00 cloth with 40% PS discount.)

The book is a well-illustrated, beautifully crafted large folio that contains a visual treasure trove of information on the life and times of William Smith and his famous geological map first published in 1815. The large format allows for some fine reproductions of the 15 individual sheets of the original, based on an original map (1816) housed in the Oxford University of Natural History. The book is organized into four grand segments represented by the corresponding map sheets: 1) borders and the north, 2) Wales and central England, 3) East Anglia and the southeast, and 4) the west. Embedded within these four sections are seven essays by individual authors that describe various aspects of Smith’s life and accomplishments: apprentice, mineral prospector, field work, cartographer, fossil collector, well sinker, and mentor. In addition, there are plenty of other geological maps, illustrated geological sections, fossils, and various other historical memorabilia scattered throughout, ending with a set of portraits sketched by Smith himself.

The fully assembled Smith map itself is quite impressive, even today. It’s huge: 8 feet, 6 inches high and 6 feet wide. (If memory serves me correctly, at the Geological Society of London offices in Piccadilly, it hangs behind a curtain in the stairwell leading up to the library on second floor.) Can this book stand in as a substitute for the real thing? I think the answer is yes, maybe even more so, because the large format means each of the 15 sheets is reproduced at almost two-thirds of the original. So, if you purchase the book you will have the luxury of examining the map at your leisure at a level of detail that is not that far off from the original. If one is a student in the history of the science of geology or paleontology, then there is no reason not to have a copy of Strata at hand. For those that teach courses such as Historical Geology or Stratigraphy, I would recommend this book. It helps to read through a reference work like this to remind us of who was William Smith and what did he do. At least for me, reading through the essays on his life’s work helped to generate a deeper understanding of the importance of the map to the discipline of historical geology. I did not realize before the importance of color shading in the original that helps to convey a three-dimensional effect to adjacent strata. When you look at these nice versions of the map, the darker edges of each colored swatch give a sense of the overlying nature of that strata. This was, of course, before strike and dip symbols were added to geological maps. Smith’s map was not the first to use colors to designate geological strata on a map. Cuvier and Brongniart published their map of the Paris Basin in 1811, but Smith brought the beginnings of biostratigraphy into play as he used fossils to characterize each of the geological formations displayed in the map. Overall, the book is a wonderful resource for anyone interested in the history of geology and especially in the foundation of historical geology.